Is gender identity considered in criminal sentencing? It certainly was in the recent case of R. v. MacDonald, 2013 NSSC 255. In this case of “house sitting gone awry,” Jesiah MacDonald, a 25-year-old transgender man, was the caretaker of a house. That in itself was no crime; however, part of his job was to care for and water the 46 marijuana plants in the house. When a search warrant was executed on the home, he was charged with production of marijuana contrary to the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, which carries a maximum sentence of 14 years in prison. Mr. MacDonald entered an early guilty plea, and immediately divulged the name of the owner of the premises. He also had significant community involvement, no criminal record, and there was evidence that he used marijuana to combat the effects of Crohn’s disease.

Part of Mr. MacDonald’s motivation for committing the crime, as was noted in the decision, was to pay for sex reassignment surgery, which was not covered in Nova Scotia at the time. (That changed in June of 2013 when Nova Scotia became the eighth province to fund sex reassignment surgery.) The crown sought 30 days of incarceration and a term of probation; the defence sought probation and a fine.

In sentencing Mr. MacDonald, Nova Scotia Supreme Court Justice Nick Scaravelli considered the purpose and principles in sections 718 to 718.2 of the Criminal Code which require weighing principles such as deterrence and denunciation with the gravity of the offence and the rehabilitation of the offender. Justice Scaravelli indicated that, absent unusual circumstances, sentences for even first-time offenders in such cases usually resulted in conventional jail time, or a conditional sentence (which was no longer available). Appropriately (and thankfully for Mr. MacDonald) Justice Scaravelli found that there were unique circumstances in the case:

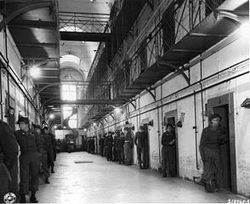

Transgender people who are sentenced to federal institutions are discriminated against from the outset — they are assigned to an institution based on their anatomy, rather than identity.

“I do not doubt that changing one gender’s identity is a life-altering and difficult process. The offender is a member of the trans gender community. The offender’s motive for committing the offence directly relates to the process of changing gender. The offender made a poor choice in attempting to achieve that goal.”

Justice Scaravelli also found that incarceration could result in difficulties for Mr. MacDonald as a transgendered person. In light of all of the circumstances, Mr. MacDonald was sentenced to probation and a fine.

This case raises the question of whether gender identity is a consideration in sentencing. Some research of reported Canadian decisions revealed five cases in which transgender identity was mentioned in some regard, and two cases (in addition to Mr. MacDonald’s) where it seems to have been a significant consideration. Of course, this research did not reveal how often it was not considered in reported decisions, or whether it was considered in unreported decisions. Even still, seven cases seems low considering that a U.S. statistic has reported that 16 per cent of transgender people have been incarcerated at some point.

One case that gave due consideration was R. v. Tideswell, [1997] O.J. No. 374. The offender in this case was sentenced for break and enter, theft of a motor vehicle with a knife, harassment and a variety of other charges. The Court noted that the incidents arose prior to the accused’s sex reassignment surgery, and that since the surgery, her behaviour stabilized. In sentencing the accused to 18 months incarceration, the Court also found that, given the accused’s gender identity, “…extended imprisonment in the subculture of a Federal Penitentiary would constitute punishment well beyond imprisonment.”

Unfortunately, this statement is all too accurate. Not only do transgender people face more discrimination and higher rates of abuse and violence while incarcerated, transgender people who are sentenced to federal institutions are discriminated against from the outset — they are assigned to an institution based on their anatomy, rather than identity. Correctional Services’ Health Services Policy states that, “Pre-operative male to female offenders with gender identity disorder shall be held in men's institutions and pre-operative female to male offenders with gender identity disorder shall be held in women's institutions.” It seems that to Corrections Canada, it does not matter how you identify, rather it is but how you look that determines where you are placed. A frightening prospect for those whose gender identity does not match up with their anatomy.

A case in point was the situation that Avery Edison recently found herself in. Ms. Edison, a U.K. comedian who had overstayed a prior student visa in Canada, was detained by Canada Border Services when she attempted to re-enter the country. Despite being legally identified as female in her U.K. passport and identification, she was initially detained in a male-only facility while awaiting her inadmissibility hearing because she was pre-operative and still had male genitalia. She tweeted the experience as officials were trying to figure out where to place her, and, thanks to social media, an international outcry erupted when she was sent to a male facility. After about 17 hours, she was transferred to a female institution before being allowed to fly home following an admissibility hearing.

So while cases like R. v. MacDonald can be lauded as a victory for transgender rights, situations such as Ms. Edison’s serve to highlight the need for further reform.

Triangle [the publication of the Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Conference of the Canadian Bar Assocation] co-editor Dorianne Mullin is a lawyer with the Nova Scotia Department of Justice

RSS Feed

RSS Feed